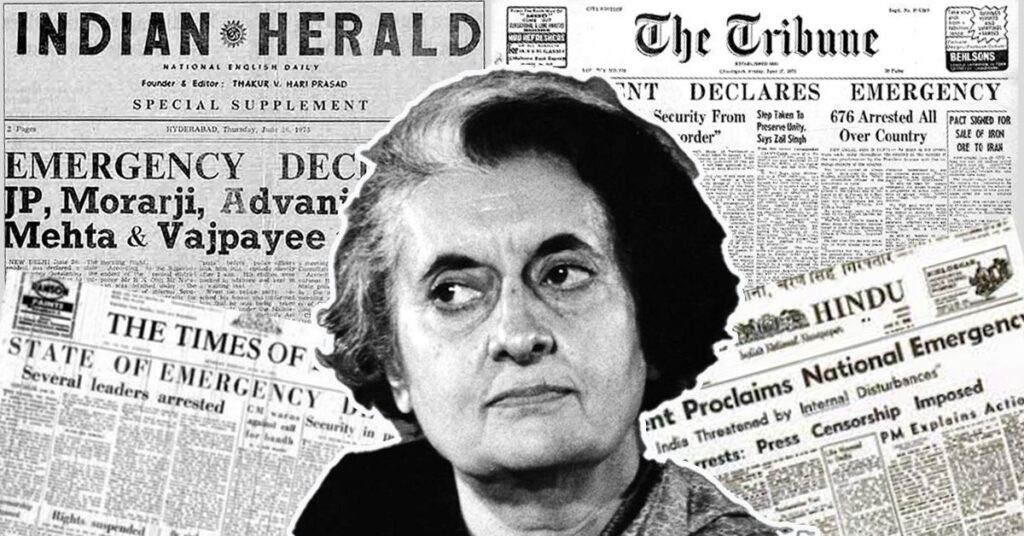

In the early hours of June 26, 1975, millions of Indians woke up to an unsettling announcement on All India Radio:

‘The President has proclaimed Emergency. There is nothing to panic about.‘

These words, spoken by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, marked the beginning of a 21-month-long period of centralised authoritarian rule in India (Guha, 2007). The Emergency, declared under Article 352 of the Constitution, led to over 21 months of democracy being effectively suspended, with press censorship, mass arrests, and sweeping executive control reshaping the nation’s political landscape (Shah Commission Report, 1978). What remains debated today is not just the legitimacy of Gandhi’s decision but the dangerous precedent it set for Indian democracy.

How Did the Emergency Come About?

By the mid-1970s, Indira Gandhi’s once-unquestioned dominance was eroding under multiple pressures. The economy was faltering, with soaring inflation and unemployment exacerbating public unrest (Khosla, 2020). Political opposition, led by movements in Gujarat and Bihar, was growing stronger, with veteran socialist Jayaprakash Narayan (JP) spearheading calls for Gandhi’s resignation (Guha, 2007). The tipping point, however, came on June 12, 1975, when the Allahabad High Court found Indira guilty of electoral malpractice and invalidated her 1971 Lok Sabha victory (State of Uttar Pradesh v. Raj Narain, 1975).

Facing a judicial verdict that could unseat her, she invoked Article 352, citing “internal disturbances,” a term vague enough to justify any executive overreach (The Emergency, 1975-77, Shah Commission Report, 1978). In reality, the biggest disturbance to her government was not external anarchy but an internal loss of power (Guha, 2007).

The Emergency: A Dictatorship in Democracy

During the Emergency, civil liberties were virtually erased. Fundamental rights under Articles 14, 19, 21, and 22 were suspended (Sathe, 2002). Opposition leaders, activists, and students were arrested under preventive detention laws, with estimates suggesting over 100,000 political prisoners (Shah Commission Report, 1978). The press was muzzled, and newspapers were required to submit their content for government approval before publishing (The Indian Express, 2017).

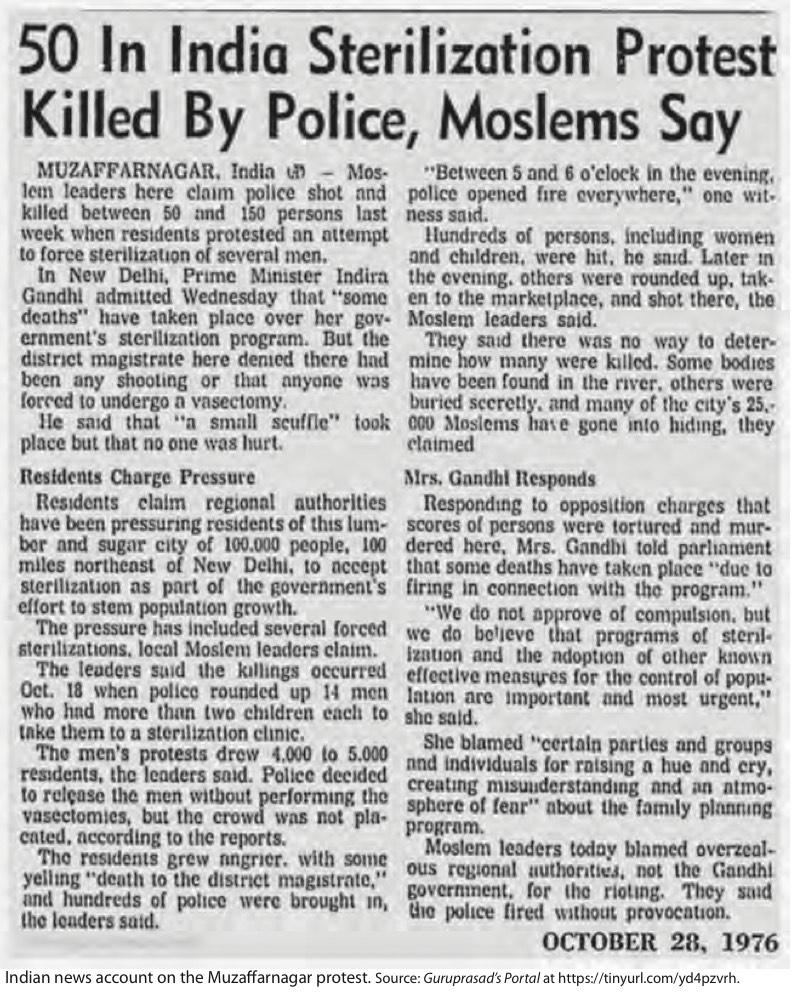

Perhaps the most chilling legacy of this period was the forced sterilization drive led by Sanjay Gandhi, Indira’s son and unelected power center. Millions of men, particularly from marginalized communities, were coerced into sterilization under the guise of population control (Shah Commission Report, 1978; Guha, 2007). Resistance to such policies was met with brute force, and a climate of fear pervaded everyday life (Khosla, 2020).

In the ADM Jabalpur v. Shivkant Shukla (1976) case, the Supreme Court shockingly ruled that during an Emergency, even the right to life and liberty was not absolute (ADM Jabalpur v. Shivkant Shukla, 1976). This moment marked one of the darkest betrayals of India’s constitutional promises, as the judiciary, meant to act as the last safeguard against tyranny, instead legitimized it (Sathe, 2002).

Was the Emergency Justified?

Some argue that the Emergency restored administrative efficiency, controlled labor strikes, and improved law and order (Guha, 2007). Supporters claim that India’s economic stability and policy execution saw temporary improvements (Khosla, 2020). However, this supposed stability was achieved by silencing the voices of millions, proving that order at the cost of democracy is not a victory but a regression (Sathe, 2002).

If we view the Emergency not as an isolated event but as a warning, it raises critical questions. What allowed such an event to unfold in the first place? Was the legal framework too weak, or was it merely exploited by those in power? If democracy could be suspended once, could it happen again under different circumstances? Could modern populist governments, armed with advanced surveillance and legal loopholes, execute a similar consolidation of power in the name of security (Khosla, 2020)?

Student Reflections: The Legacy and Its Echoes Today

For students studying law and history in modern India, the Emergency is a case study in how democracies fall from within, not through external conquest but through internal compromise. It forces us to ask whether constitutional safeguards are truly effective if an individual can override them with the right justification (Sathe, 2002). The judiciary’s complicity in ADM Jabalpur is a lesson that courts are not inherently guardians of justice—they are only as independent as the principles they choose to uphold (ADM Jabalpur v. Shivkant Shukla, 1976). If the Supreme Court in 1976 could rule that the government had the right to deny citizens the right to life, what stops a future government from doing the same under different pretenses (Khosla, 2020)?

Some students argue that the 44th Constitutional Amendment (1978), which restricted Emergency powers, was enough to prevent history from repeating itself (Shah Commission Report, 1978). But others point out that laws are only as strong as the leaders who implement them. If the courts and the bureaucracy could submit to authoritarian rule once, could they do so again under a different ideological banner (Sathe, 2002)? Does the rise of hyper-nationalism and state control in some countries today mirror the justifications used in 1975 (Guha, 2007)?

The Emergency—it is not an event of the past but a precedent for the future. Laws were changed, and the political landscape shifted, but the fundamental truth remains: democracy is fragile. It does not collapse overnight; it is chipped away, one justified decision at a time, until people wake up and realize it is gone (Khosla, 2020). The question we must ask is not whether we remember the Emergency but whether we have truly learned from it.

Conclusion

The Emergency remains India’s greatest constitutional crisis, a period that tested the strength of its institutions and exposed the dangers of unchecked executive power (Guha, 2007). Indira Gandhi’s decision to impose it may have been driven by immediate political survival, but its implications reached far beyond her tenure (State of Uttar Pradesh v. Raj Narain, 1975). The post-Emergency reforms, particularly the 44th Amendment, sought to prevent such overreach in the future, but legal safeguards are not enough without political and public vigilance (Shah Commission Report, 1978).

At a time when democratic backsliding is a global concern, the lessons of 1975-77 remain more relevant than ever. The Emergency was a reminder that democracy is not self-sustaining. It requires constant protection, an informed citizenry, and a judiciary that serves the people rather than the government (Khosla, 2020).

If we fail to recognize this, history does not need to repeat itself; it will simply evolve under new justifications.

References

- State of Uttar Pradesh v. Raj Narain, AIR 1975 SC 865.

- ADM Jabalpur v. Shivkant Shukla, AIR 1976 SC 1207.

- Guha, Ramachandra. India After Gandhi: The History of the World’s Largest Democracy. HarperCollins, 2007.

- The Emergency, 1975-77: Report of the Shah Commission of Inquiry. Government of India, 1978.

- Khosla, Madhav. India’s Founding Moment: The Constitution of a Most Surprising Democracy. Harvard University Press, 2020.

- Sathe, S.P. Judicial Activism in India: Transgressing Borders and Enforcing Limits. Oxford University Press, 2002.

- “Indira’s Emergency: The Darkest Period of Indian Democracy.” The Indian Express, 2017.

Incredibly thought-provoking.

The bit about precedents being established to the modern society, worldwide, was particularly well written. Food for thought.